March 3, 2021

Until recently, even leading scholars weren't aware that the British-born Mexican Surrealist Leonora Carrington had created her own tarot deck. Curator Tere Arcq was conducting research for a 2018 retrospective of Carrington's work at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City when she unearthed it: a suite of 22 major arcana cards made around 1955, hand-painted with oil on squares of hard board and accented with delicate applications of gold and silver leaf. The Tarot of Leonora Carrington, a new book with contributions from Arcq, art historian Susan Aberth, and Carrington's son Gabriel, takes stock of - and in the case of the limited-edition version, comes with a facsimile set of - this deck.

Occultism, the book demonstrates, was thoroughly knit into the fabric of Carrington's life. The artist grew up surrounded by Celtic fairy tales, yarns spun by her family's Irish matriarchs. As a painting student in London, she became fascinated with alchemy. She went on to establish herself as a preeminent Surrealist in France, where with her peers she mined manifold mystical practices in search of alternative forms of knowledge. By the time Carrington relocated to Mexico in 1942, she was well-versed in astrology, alchemy, Kabbalah, mythology, witchcraft, and tarot - topics that would bond her to her friend and fellow Surrealist expat Remedios Varo, as well as Octavio Paz, Alejandro Jodorowsky, and María Félix. Carrington both built community through occultism and gravitated toward the possible worlds that the occult envisioned. When she read Robert Graves's The White Goddess, about a mythic ancient matriarchal society, in 1948, she described the experience as "the greatest revelation of my life."

Carrington's tarot cards are populated by her characteristically fey figures, often androgynes or human-animal hybrids, set against backdrops in deep, full hues: cobalt, lapis, mulberry, gold. She drew upon archetypal decks including gilded examples from 15th century Italy, the Tarot of Marseilles beloved by many Surrealists, and the popular Rider-Waite deck from 1909. The book puzzles over the artist's additions and omissions in relation to these predecessors, using biographical cues and a knowledge of visual symbolism to "read" her cards - not so unlike a tarot card reader. In Carrington's Chariot card, two female creatures who normally face away from one another face toward one another, bound by a heart; the authors suggest that choices like this one reflect the artist's belief in feminized collaboration, which was tied up with her contributions to the feminist movement and her love of goddess lore alike.

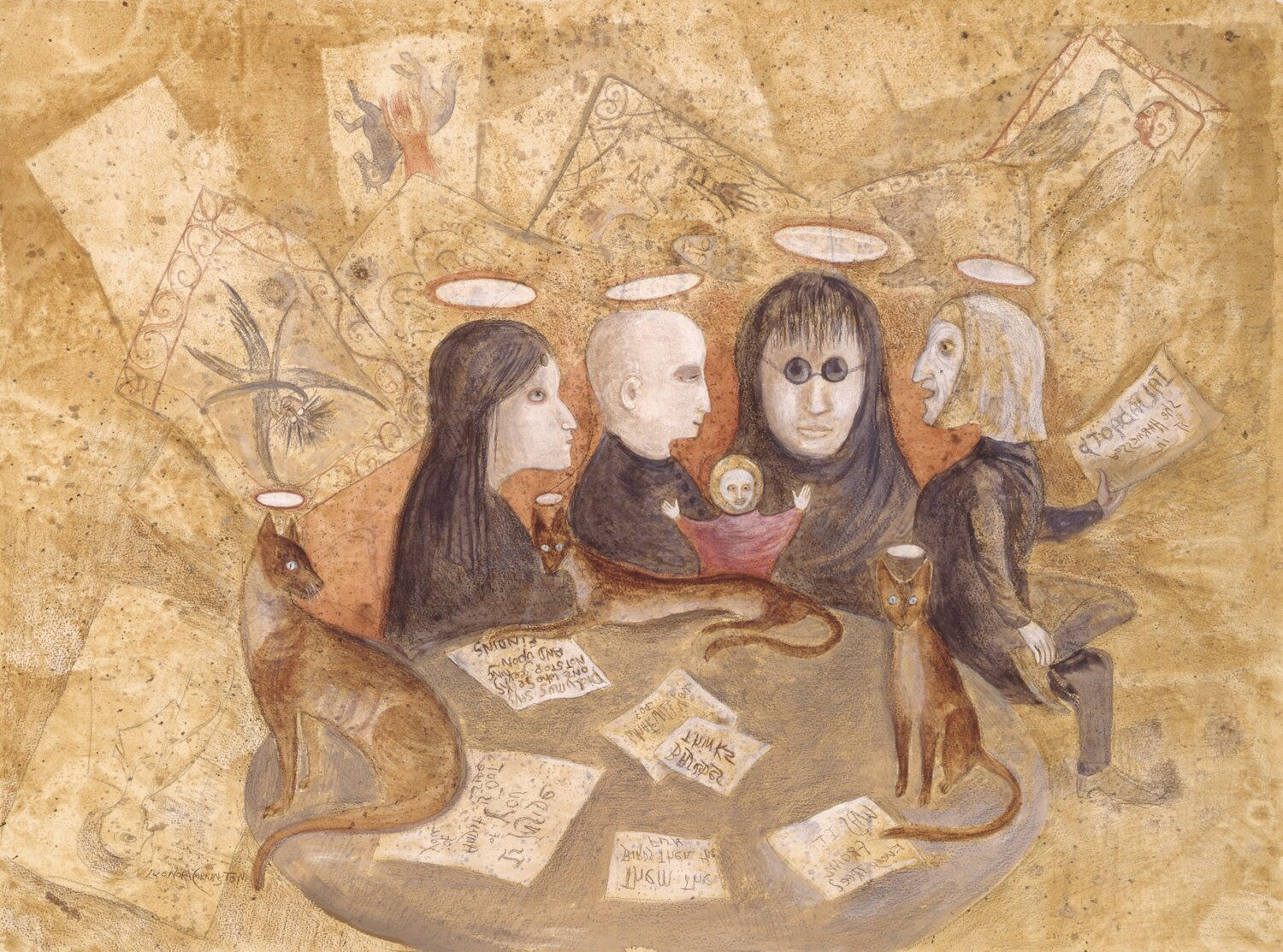

The book's analysis of drawings and paintings spanning Carrington's career elucidates that tarot iconography was likewise an animating force in her artwork. Some references are overt, as in her 1995 drawing of people at a table with tarot cards. Others are more coded: two self-portraits from 1949 and 1973 riff on the Hermit card, which traditionally depicts a lone figure with a lantern to denote - among other things, tarot cards being endlessly interpretable - the frequently isolating work of introspection. In one self-portrait, Carrington paints herself as a poncho draped over a coat rack; in the other, her lantern contains a parrot instead of a flame. A sense of play and imagination, a fundamental openness to alternative ways of being, was always Carrington's guiding light.

The Tarot of Leonora Carrington (Fulgur Press, 2021), by Susan Aberth and Tere Arcq, is now available on Bookshop.