by Eileen Kinsella

8 May 2024

Cuban-born artist Enrique Martínez Celaya was just six years old in 1971 when his mother gave him a notebook with an image of Diego Velazquez’s famous 17th-century Portrait of a Little Girl gracing the cover. At the time, he was the same age as the titular little girl depicted in the painting.

That moment cemented his connection with the portrait’s subject, long before he knew that Velazquez was one of the most important artists in history. Later, while living in Madrid as an adult, the artist deepened his connection further with frequent visits to the Museo Nacional del Prado that “strongly influenced Martínez Celaya’s artistic journey,” according to the Hispanic Museum and Library, where a show based on that relationship, aptly titled, “The Word-Shimmering Sea: Diego Velázquez / Enrique Martínez Celaya,” is on view through July 14, 2024.

The show was curated by the artist himself along with Hispanic Society director and CEO Guillaume Kientz, and is described as an immersion into Martínez Celaya’s childhood notebook. It aims to create a dialogue about “the conditions and imaginations of childhood, exile, the promised land, the flow of time, the refuge offered by language and the nature of painting.” The notebook includes handwritten letters from Martínez Celaya to his father, who was living in Spain at the time, before he and his family in Cuba joined him.

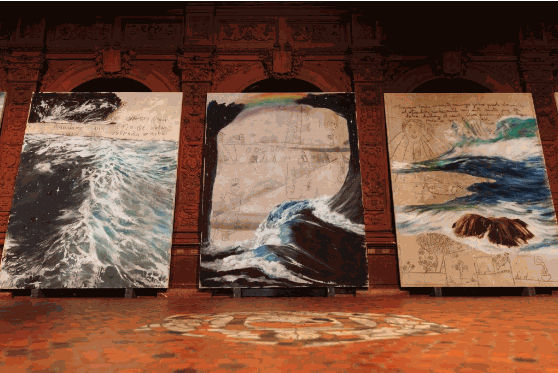

“The Word-Shimmering Sea” features blown up versions of Martínez Celaya’s childhood letters on canvas drop cloths that are layered with the history of work and paint, which is superimposed with painted fragments of the sea. They include large-scale paintings of childhood letters, as well as small paintings based on Velázquez’s Little Girl, a wooden sculpture of a boy holding the artist’s first grade notebook, projections of elements from the notebook onto the ceiling and strings of paper boats made by schoolchildren in the artist’s childhood town of Nueva Paz, Cuba.

We caught up with the artist on the eve of the debut to get a view into his Los Angeles studio and talk about his preparations for this major new show.

Tell us about your studio. How does it compare to other studios you’ve had?

My studio is in Jefferson Park, a neighborhood located a few miles southwest of downtown Los Angeles, which is an area of industrial warehouses, small commercial buildings, and Arts & Crafts bungalows. My building is a large space with good light and tall ceilings originally built in the 1950s for manufacturing. I re-modeled it to support the way I work, including planting trees and a garden, and building a library.

I’ve enjoyed designing and re-modeling all my studios, and in this one I incorporated many of the lessons from things that succeeded and failed before. I want the studio to resist comfort and support working, thinking, and also silence, so it has the combined feeling of a workspace, a monastery, and a laboratory.

What kind of atmosphere do you prefer when you work?

My process depends on moving between writing and the studio. I like silence when I write, and while working in the studio, I usually listen to music. Sometimes, usually when I’m drawing, sanding, or scraping, I listen to a talk on physics or philosophy. I keep notes, pictures, poems, drawings, and other things over my painting table. These are not mementos, but navigation guides—reminders of the things I want to think about.

When you feel stuck while preparing for a show, what do you do to get unstuck?

I don’t like formulaic or repetitive work. They make me feel I’ve hired myself to do a life-sucking task. I’m interested in work that exhausts or quickly disposes with what I know, which is why I’m often on the verge of failing in the studio. When working on a new exhibition of painting, I don’t ask, “What can I paint?” but rather, “What is painting?” Which is why getting stuck, or at least spending time using or removing obstacles, is what I expect when I arrive at the studio each morning. To get somewhere, I use writing, reading, or tidying the studio. I find that sweeping is a good source of insights and surprises.

How did your studies and experience as a physicist inform your artistic practice?

Since childhood, I have been curious about the world and about the choices we make. This curiosity led me to physics, literature, and art, so there’s an old connection between them for me.

I’m very grateful for my training in physics. Physics and mathematics are beautiful and remarkable in their capabilities, and they encourage humility and reason, which most of us could use. But there are many questions that don’t matter to science that are urgent to me, which is why I left my active work in science. As time passes, my ability to do the math on which my physics work depended becomes rustier, but the curiosity for science is still there—it might have grown.

It could be confusing to reference science in general conversation, and in an art context in particular. A lot of what is said about the relationship between science and art is superficial and full of stereotypes and unexamined assumptions, and artists and scholars in the humanities sometimes reference science they don’t really understand because it lends the appearance of intelligence and rigor to their work. Our need to seem intelligent or intellectual is unfortunate, in part because it’s so limiting. One way my training in science informs my work is by giving me confidence in what the arts and humanities offer. Perhaps this doesn’t seem like a significant influence, but the freedom it provides is a valuable gift of my scientific training to my artistic practice.

I also continue to write and talk about art and science. For instance, three days after the opening of my exhibition at the Hispanic Society, on April 21, I spoke with Roald Hoffmann, a Nobel Prize chemist and poet, about art and science at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Is the Hispanic Society show one of the biggest you’ve staged? How have your preparations for this show differed from previous exhibits?

In terms of the number of elements, my project for SITE Santa Fe, “The Pearl,” had more, and in terms of size, my installations at the Berliner Philharmonie, or the one currently at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Cuba, “Los muertos llaman al alba,” were larger. But the show at the Hispanic Society is the most wide-reaching and varied. It incorporates seven large paintings of the sea, four smaller paintings responding to Velásquez’s “Little Girl,” a burnt wood sculpture of a boy, projections, letters I wrote to my father when I was six years old, a very moving painting by Velázquez, paper boats made by the children of my elementary school in the small town in Cuba where I was raised, my first-grade notebook, pine cones from the beach town where I went to recover from asthma, as well as other work from the museum’s collection related to childhood and exile.

The preparations for this installation differed from past projects in that they required much time reflecting on the connections between all the elements while simultaneously working outside of the studio to understand, create, or secure them. It is also different because the source is more personal than any other project I have done, and since my goal is never my story, I had to find something beyond myself in what might seem like a very personal narrative.

You are also a prolific author. How does your writing and art making practice overlap and inform one another? And how are they separate?

When I first realized there was more to art than my childhood paintings, it was literature that provided my initial emotional and intellectual education, and it is to literature that I often return to remember why I am an artist. I mentioned before that writing is part of my working process in the studio, but I also write independently of those uses. For the most part, I write essays and something like poetry, and I’m now finishing a novel that has been the underlying consciousness behind many of the exhibitions and studio work of the last two decades.